Editor’s Note

With the papal conclave set to begin on May 7, 2025, after the death of Pope Francis, and the Camerlengo’s interim administration of the Vatican nearing its close, the Church—and the world—awaits the emergence of a new pope. In this moment of transition, we turn back to the life and rule of Pope Francis, a reluctant pontiff who nevertheless governed the Vatican and the Holy See with the steely tactical discipline one might expect from a Jesuit forged in the fires of Argentina’s Dirty War.

Francis was no mere spiritual figurehead. He was an operator: a man who navigated dictatorship, ecclesiastical bureaucracy, and global crises with the calibrated poise of someone who understood both power and its limits. His whispered remark to Cardinal Hummes upon election—“May God forgive you for what you have done”—wasn’t just self-effacing humor. It was a signal. Francis had not sought the throne of Peter, but he would occupy it with a mix of humility and ruthlessness that came to define his papacy.

Executive Summary

- Outsider Turned Insider: Pope Francis (Jorge Mario Bergoglio) rose from a Jesuit background in Argentina to become an unlikely pope, bringing an outsider’s perspective into the Vatican’s corridors of power. His formation in the Society of Jesus—an order once viewed with suspicion by the Church’s hierarchy—imbued him with a unique mix of spiritual fervor and tactical shrewdness. This Jesuit-trained acumen helped Francis navigate and ultimately dominate the very Roman bureaucracy that many thought would tame him.

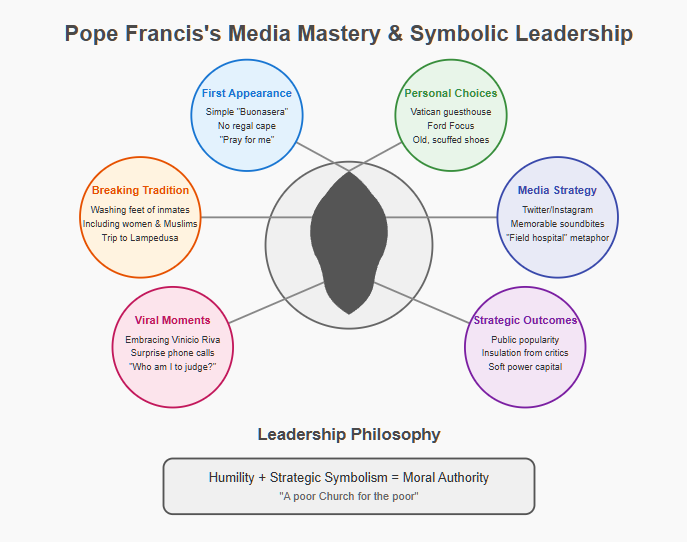

- Humble Persona, Strategic Messaging: Francis cultivated a global image as a humble servant, using simple words and powerful symbolism to charm the world’s media. From the first moment he appeared on the papal balcony with a casual “Buonasera” (“Good evening”) to washing the feet of prisoners (including women and Muslims) in a youth detention center, he signaled a break from papal pomp and emphasized mercy over protocol. These gestures were not mere piety—they were calculated acts of communication that advanced his agenda and inoculated him against critics, making him a master of soft power on the world stage.

- Institutional Reformer: Tasked with cleaning up an unwieldy Curia and a scandal-tainted Vatican bank, Francis proved to be an unsparing reformer. He overhauled the Vatican’s financial structures with a two-pronged approach: technical reforms (streamlining departments, imposing transparency, and new anti-corruption mechanisms) and cultural change (fostering a mindset of service through “synodality”). Despite fierce resistance from entrenched interests – including open infighting among cardinals in 2015 – he persisted. He put a stop to decades of mismanagement by empowering new oversight bodies like the Secretariat for the Economy, cleaning out dormant bank accounts, and even hauling a once-powerful cardinal into Vatican court for financial crimes. His 2022 constitution Praedicate Evangelium cemented many of these changes, opening top Curial roles to laypeople and recalibrating the Curia’s role as one of service rather than domination.

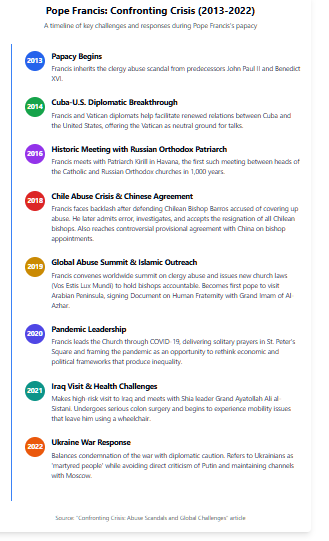

- Crisis Management and Diplomacy: Francis confronted crises with a combination of decisiveness and diplomacy. In the clerical sexual abuse scandal, he oscillated between early missteps and bold corrective action – initially botching a notorious case in Chile, then rebounding by apologizing, removing bishops, and convening a global summit on abuse. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he led with pastoral compassion, standing alone in an empty St. Peter’s Square to implore solidarity in the face of a “storm” all humanity must weather together. On the world stage, he was a skilled diplomat without an army: cutting secret deals and building bridges. He brokered a historic rapprochement between the U.S. and Cuba in 2014, struck an unprecedented (if controversial) accord with China’s Communist government over the appointment of bishops, met with Russia’s Orthodox patriarch and attempted delicate mediation in conflicts from Ukraine to South Sudan. Francis’s geopolitical strategy was one of engagement over isolation – a pragmatic posture that earned him both praise as a peacemaker and criticism for being too conciliatory with autocrats.

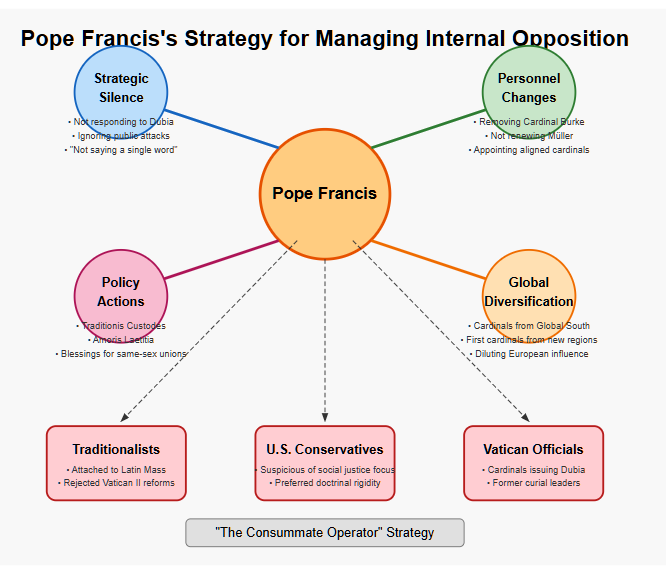

- Neutralizing Internal Opposition: Inside the Church, Francis faced ferocious opposition from traditionalist and ultraconservative factions who viewed his papacy as a threat to established doctrine and privilege. Cardinals and commentators accused him of everything from sowing confusion to outright heresy. The “Dubia” letter of 2016, in which four cardinals challenged him, and a 2018 clerical broadside urging his resignation marked unprecedented open dissent. Francis responded with strategic calm – often meeting attacks with silence – while quietly outmaneuvering his rivals. He shuffled outspoken critics out of influential positions, elevated a new generation of cardinals loyal to his vision, and even issued a shock rebuke to traditionalists by restricting the old Latin Mass when he felt they threatened Church unity. His Jesuit instinct for the long game ensured that opponents were marginalized and the reformist course stayed steady.

- Legacy of a Consummate Operator: Pope Francis leaves behind an altered institutional landscape and a reoriented global Church. He shifted the Catholic Church’s posture closer to the margins of society – “a field hospital after battle,” as he liked to say – tending to the wounded while resetting priorities on social justice, the environment, and humility in governance. Structurally, he transformed the College of Cardinals by naming representatives from far-flung corners of the world (often bypassing the traditional European power centers) and thereby stacking the deck for the next conclave toward continuity of his policies. Doctrinally, without changing core dogma, he achieved subtle yet profound developments: rejecting the death penalty as inadmissible, cautiously opening the door for divorced-and-remarried Catholics to return to Communion, and normalizing the idea that the Church can adapt pastorally without losing its identity. His papacy’s end finds the Church at a crossroads – imbued with Francis’s reforms and inclusive spirit, but also riven by tensions he sought to resolve. The consummate operator in Francis ensured that the forces of change have taken root; how deeply they will grow remains the strategic question for his successors.

Background and Formation

Jesuit Origins and Early Leadership: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s journey to the papacy began in the Society of Jesus, an order famed for discipline, intellectual rigor, and a history of savvy political maneuvering. Born in Buenos Aires in 1936 to Italian-immigrant parents, young Bergoglio was shaped by Latin American Catholicism and the rigorous spiritual training of the Jesuits. He entered the novitiate in 1958, drawn by the Jesuits’ reputation for operating on “the front lines” of the Church’s mission. Jesuits take an extra vow of obedience to the pope, and their internal culture often resembles a martial esprit de corps. This background instilled in Bergoglio a potent blend of obedience and initiative – a willingness to go anywhere and do anything “for the greater glory of God,” yet also a keen sense of strategy in service of the faith. Notably, as a member of an order once suppressed and later distrusted by Rome, he developed an outsider’s sensibility toward centralized power. Indeed, future Pope Francis “may act like a Franciscan, but he thinks like a Jesuit,” as one colleague quipped, highlighting the subtle calculating mind behind his humble outward persona.

Trials in Argentina’s ‘Dirty War’: Bergoglio’s leadership skills were forged under extreme pressure. In 1973, at just 36 years old, he was appointed Provincial Superior of the Jesuits in Argentina – precisely as the country descended into turmoil. The 1976–1983 military dictatorship (the “Dirty War”) saw tens of thousands disappeared or killed, including priests who advocated for social justice. Caught between a brutal regime and endangered clergy, Bergoglio walked a tightrope. By his own later admission, he made decisions “abruptly and by myself,” exhibiting an authoritarian and quick manner that earned him both loyalty and enmity. He fully embraced the Jesuits’ post-Vatican II turn to the poor, yet opposed Marxist-inspired liberation theology, trying to steer a middle course that left him accused by some of being too conservative, even a collaborator. The most damning allegation came from two Jesuit priests who were kidnapped by the junta in 1976 – critics charged that Provincial Bergoglio had withdrawn his protection from them. While “the evidence is sketchy and contested” on this matter, later investigations and biographies indicated Bergoglio was working behind the scenes to save persecuted people, hiding some and lobbying for the release of others. In fact, one author documented how the future pope “saved as many as a thousand” people during the dictatorship by covert means. Argentine courts ultimately never found wrongdoing on his part, and he was cleared of accusations of complicity. Nevertheless, the period scarred him. Internally, Jesuit superiors in the 1980s saw Bergoglio as divisive; he was relieved of duties and effectively exiled to Córdoba for a time of penance and reflection. This “time of great interior crisis” humbled him, teaching lessons in patience and compromise that would later mark his governance style.

Rise as a Reform-Minded Bishop: Paradoxically, Bergoglio’s rocky tenure as a Jesuit provincial paved the way for his rise in the Church’s hierarchy. Accepting his exile with characteristically Jesuit obedience, he waited – and was thrown a lifeline in 1992 when Cardinal Antonio Quarracino, impressed by Bergoglio’s pastoral work, plucked him from the periphery to be an auxiliary bishop of Buenos Aires. “Maybe a bad Jesuit can become a good bishop,” went the wry joke among Argentine Jesuits at the time. Indeed, Bergoglio flourished as a bishop. By 1998 he succeeded Quarracino as Archbishop of Buenos Aires, inheriting a huge, complex diocese marked by stark inequality. On the streets and in the slums, he cultivated a reputation for personal simplicity and compassion: riding the bus, cooking his own meals, and famously visiting the villas miseria (shantytowns) to minister to the poor. These habits earned him the nickname “Padre Villas” (Father of the Slums) and later “the slum bishop,” endearing him to the populace. But Bergoglio was no naïve social worker; he also proved a deft operator in Church politics. In 2001, Pope John Paul II made him a cardinal – one of only two Jesuits in the College of Cardinals at the time. In the 2005 conclave that followed John Paul’s death, Cardinal Bergoglio reportedly became the runner-up, nearly elected pope as a compromise candidate when factions were deadlocked. That near miss, however, “left many Jesuits breathing a sigh of relief.” Within his own order, some still viewed him with suspicion for his meteoric rise and independent streak. Little did they know that within eight years, their “rejected” Jesuit brother would don the white cassock.

Shaped by Jesuit Spirituality: Bergoglio’s Jesuit formation left an indelible mark on his leadership style as Pope. The Jesuits’ ethos of being “contemplatives in action” – combining prayerful discernment with bold action – became a hallmark of Francis’s decision-making. He often spoke of undergoing discernment (a kind of spiritual strategizing) on major decisions, and he favored consultative approaches reminiscent of Jesuit community deliberations. Yet, when the moment for action arrived, he could act unilaterally and swiftly (a trait honed during the Dirty War). His early mistakes as a provincial taught him, as he later reflected, the dangers of impetuosity and the need for mercy. This translated into a papal style that was personally kind and flexible, but institutionally unafraid to wield authority when required. Moreover, having been an insider-outsider – a high-ranking prelate who was still mistrusted by the Church’s old guard – Francis had few illusions about how power works in Rome. He understood the curial mindset but did not fetishize it. This background set the stage for a papacy that would be, in essence, a reformer’s reconquest of the Vatican, carried out by a man who had learned about power the hard way and survived ecclesial wars long before he ever stepped foot in the Apostolic Palace.

Media Mastery and Symbolic Acts of Leadership

From the outset of his papacy in March 2013, Pope Francis proved extraordinarily adept at using symbolic gestures to project power and set a narrative. Unlike leaders who rely on formal authority alone, Francis understood the value of imagery and simplicity in winning hearts and disarming opponents. His very first appearance as pope exemplified this: stepping onto the balcony above St. Peter’s Square, he eschewed the regal fur-trimmed cape worn by his predecessors and simply greeted the crowd with “Buonasera” (good evening). That one informal word – delivered with a humble wave – spoke volumes. It signaled that a different kind of pontificate had begun, one less formal and more connected to ordinary people. He followed by asking the people to bless him before he imparted his blessing, a startling role reversal that endeared him to the world press and faithful alike. As one commentator noted, Francis “opened his papacy not with a proclamation, but with a quiet request: ‘Pray for me.’” This instant rapport-building was no accident; it was the first move in a carefully considered strategy to build moral credibility and popular support, which in turn gave him leverage to tackle tougher issues within the Church.

In the first months of his reign, Francis deployed one iconic act of humility after another. He declined to move into the opulent Papal Apartments, choosing instead to live in the sparse Vatican guesthouse (Casa Santa Marta) among other residents. He rode in a simple Ford Focus and kept wearing his old scuffed shoes rather than adopting the papal red loafers. These personal lifestyle choices were highly publicized and contrasted sharply with the image of a European prince-pope. They conveyed authenticity and aligned with his message of a “poor Church for the poor.” More dramatically, just two weeks after his election, on Holy Thursday 2013, Francis went to a juvenile prison and washed the feet of twelve inmates, including two women and two Muslims – a papal first. Previous popes had restricted the foot-washing ritual to Catholic men (often priests) in ornate basilicas; Francis not only brought the ritual to the margins but literally included the marginalized. In doing so, he sent an unmistakable message of inclusion and servanthood. The Guardian noted that “all modern popes” before him had kept to tradition, whereas Francis was breaking an unwritten taboo. The images of the Pope kneeling to kiss the feet of a young Muslim woman quickly went viral, underscoring a new model of papal behavior rooted in humility. As a veteran Vatican journalist observed, from the beginning Francis “proved many times over that he wants to break away from clerical privilege, come down from St. Peter’s throne and act as a humble servant of the faithful.”

Francis’s understanding of visual and social media extended beyond staged events into spontaneous encounters. He had a knack for dramatic gestures that felt genuine rather than performative. The November 2013 embrace of Vinicio Riva (pictured above) is a case in point. In that moment – comforting a man grotesquely disfigured by disease, pressing his face against Riva’s in an expression of pure empathy – Francis generated an image that circled the globe and was compared to the compassion of his namesake, St. Francis of Assisi, kissing a leper. Vatican media later confirmed that the Pope had no prior plan for this; it was simply his instinct to stop and show mercy, which happened to be caught on camera. Yet Francis surely recognized the power of such imagery. He often said he wanted a Church that could “heal wounds” and not be afraid of the world’s messiness. That single photograph did more to advance that theme than any theological tome. Similarly, Francis made unannounced phone calls to people who wrote him letters – calls that the recipients often shared with media, adding to the legend of the “Pope who calls you out of the blue.” He posed for selfies with young pilgrims. He allowed – even encouraged – a down-to-earth tone in his off-the-cuff interviews and daily homilies, resulting in remarkably frank headlines. (When asked in 2013 about a gay person seeking God, his casual response “Who am I to judge?” became perhaps the most quoted line of his papacy, signaling a shift in pastoral tone without changing doctrine.)

Behind these populist touches was a deliberate media strategy to shift the focus of Catholic messaging. Under Francis, the Church talked less about itself (rules, authority, internal disputes) and more about the world’s pain: poverty, migration, inequality, climate change. He used his symbolic actions to amplify those priorities. For example, his first trip as pope was not to a traditional Catholic bastion but to the migrant-filled Italian island of Lampedusa in July 2013. There, he mourned thousands of African migrants who died at sea and decried the “globalization of indifference” towards refugees. The setting itself – a remote Mediterranean outpost littered with migrant coffins – and his choice to cast a wreath upon the sea in memory of the drowned, created a searing image of moral leadership on a global crisis. Likewise, in 2016, he visited the Greek island of Lesbos amid the Syrian refugee crisis and personally brought back 12 Syrian Muslim refugees on the papal plane to resettle in Rome. It was an unprecedented papal gesture that “won him wild popularity among progressives and signaled new priorities for the Vatican” in the post-Benedict era.

Francis also harnessed the power of social media and modern communications to reach a global audience. The papal Twitter account (@Pontifex) exponentially grew under him in various languages, and he frequently tweeted short spiritual messages that were retweeted by hundreds of thousands. He launched an official papal Instagram account, sharing photos that further humanized the papacy. Rather than lengthy, dense writings (though he produced those as well in encyclicals and exhortations), Francis mastered the art of the soundbite and vivid metaphor. He famously described the Church as a “field hospital after battle” – tending the wounded rather than obsessing over rules – in a 2013 interview. That phrase became a mission statement widely cited in the press. In a world saturated with information, Francis made sure his key themes (mercy, care for creation, solidarity with the poor) were carried by simple, relatable images and words. This media savvy served a strategic end: it bolstered his personal popularity to such an extent that it insulated him, to a degree, from internal Church critics. By capturing the imagination of people far beyond the Catholic fold (including secular media and world leaders), Francis accrued a form of soft power capital. Even when traditionalists grumbled about his breaking of precedents, they struggled to counter the magnetic effect he had on the public and the goodwill he had banked for the Church. As former U.S. President Barack Obama observed in a tribute, “Pope Francis was the rare leader who made us want to be better people. In his humility and his gestures at once simple and profound — embracing the sick, ministering to the homeless, washing the feet of young prisoners — he shook us out of our complacency.” By expertly melding humility with showmanship, Pope Francis used media and symbolism as a tactical weapon to advance his vision from day one.

Reformer-in-Chief: Reshaping Vatican Governance and Finances

Mandate for Reform: When Francis assumed the papacy in 2013, he inherited a Vatican bureaucracy in disarray. His predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, had left behind an “outdated Vatican bureaucracy” plagued by scandals – from the Vatileaks affair that exposed Curial corruption to financial woes at the Vatican Bank. The cardinals who elected Francis did so with a clear mandate: clean house. Francis, with his outsider credibility and no-nonsense style, took that mandate seriously. Over his decade at the helm, he executed the most significant overhaul of the Roman Curia’s structure and culture since at least the Second Vatican Council. It was an exercise in institutional power politics, as he had to break entrenched “old guard” networks, align disparate reformers, and push through new policies while keeping the Church’s day-to-day running smoothly.

Financial Overhaul amid ‘Gang Wars’: One of Francis’s first targets was the murky world of Vatican finances. Early on, he famously quipped that “St. Peter did not have a bank account”, signaling his intent to impose transparency on the Vatican Bank (formally, the Institute for Works of Religion, IOR). In 2014, he created a new Secretariat for the Economy, effectively a finance ministry, and appointed Cardinal George Pell – a blunt Australian with a mandate to crack down on corruption – as its first prefect. This office was given unprecedented authority to monitor budgets, spending, and investments of all Vatican departments, a revolutionary step in an institution historically allergic to outside oversight. The Secretariat for the Economy, overseen by a mix of clerics and lay experts, began implementing “best practices” and compiling a unified budget – things never before done in the Vatican’s centuries of operation. Francis also established an independent Auditor General position and a Council for the Economy to involve outside experts. These moves were concrete steps to end a culture of financial secrecy that had led to periodic scandals (from allegations of money-laundering to extravagant waste).

The pushback was immediate. The Pope’s efforts “were met with staunch resistance from Vatican bureaucrats,” as one account noted. Curial officials who had long enjoyed fief-like autonomy bristled at having to open their books. In February 2015, a showdown ensued: a meeting between reformers and the old guard devolved into what an Italian observer called “the same old gang war,” grinding the process to a halt amid shouting matches. Francis stood by Pell and the reformers, but the resistance only grew more cunning. In 2017, Cardinal Pell was forced to return to Australia to face charges of historical sexual abuse – charges widely seen in Rome as dubious (he was later acquitted on appeal). During Pell’s absence, the anti-reform faction struck again: the Vatican’s first Auditor General, Libero Milone, was suddenly accused of “espionage” and sacked, escorted off the premises by armed gendarmes. Milone insisted he was fired because he had begun uncovering corruption. He later alleged that Cardinal Angelo Becciu, the Substitute (deputy chief of staff) in the Secretariat of State, orchestrated his ouster after Milone and Pell discovered a secret $400 million London real estate investment controlled by Becciu and others. That investment – using funds siphoned from Peter’s Pence (charitable donations) – would become the centerpiece of the Vatican’s largest financial scandal in decades.

Francis responded to these internal coups with measured force. Rather than capitulate, he quietly removed Becciu from power in 2020, stripping him of his cardinalatial rights and launching a full investigation. By 2021, Vatican prosecutors put Becciu and several collaborators on trial for fraud, embezzlement, and abuse of office. In a striking outcome, a Vatican tribunal in 2022 found Becciu and others guilty, sentencing the once high-flying cardinal to prison (a nearly unheard-of fall from grace in the Vatican). Much of the embezzled money was never recovered, illustrating the depth of the corruption, but the trial itself sent a clear message that the papacy was done turning a blind eye. As this “trial of the century” wrapped up, Francis moved swiftly to prevent such exploits from recurring: he stripped the Secretariat of State of all its financial assets and authority, reallocating its funds and investment portfolio to other entities (like APSA, the Vatican’s central asset manager). He imposed strict new procurement regulations to control how Vatican departments spend money and to eliminate sweetheart contracts. And he installed new personnel – bringing in an experienced lay finance chief and empowering the refreshed Auditor’s office to dig through the Curia’s accounts. These were bold moves that effectively dismantled power centers that had existed for centuries within the Vatican’s administrative core.

By 2022, Pope Francis codified many reforms in the landmark apostolic constitution “Praedicate Evangelium” (“Preach the Gospel”). This new governing charter – replacing John Paul II’s 1988 constitution – was the blueprint of a Vatican for the 21st century. It reorganized and renamed Curial departments (now all called “dicasteries” instead of the hierarchical “congregation” terminology) and crucially, it opened nearly all Vatican leadership positions to lay men and women. In theory, even the Prefect of the Dicastery for Doctrine (formerly the Holy Office) or the Secretary of State could be a qualified layperson under the new rules. “This is revolutionary,” wrote one analyst, noting it shifts the Curia away from the monarchical model of popes-and-princes toward a service-oriented, collegial model envisioned by Vatican II. Francis explicitly stated in the text that the Curia is not an authority over bishops, but at the service of both pope and bishops. In other words, he tried to demote the Curia from kingmakers to support staff – “more like civil service than a governing elite,” as one commentator put it. This was a direct affront to any curial cleric who saw himself as a power broker above the local churches. Francis also used Praedicate Evangelium to firmly enshrine the role of the Secretariat for the Economy and related financial bodies, ensuring that what had been painful ad-hoc reforms are now part of Church law. The Secretariat for the Economy, backed by a council including lay financial experts, now has authority to monitor every dicastery’s financial dealings and enforce international standards of accounting. Such measures were unthinkable a decade prior, before Francis’s tenure.

While structural changes grabbed headlines, Francis knew that true reform meant changing a culture. He did not shy away from bluntly calling out the sins of the Curia to their faces. In his infamous 2014 Christmas address, he diagnosed 15 “ailments of the Curia” – spiritual maladies like the “terrorism of gossip” and “spiritual Alzheimer’s” that he said were afflicting Vatican officials. In that speech, he excoriated the “pathology of power” among those who seek worldly advancement in the Church, and the loss of humility and joy in service. The cardinals and bishops in the room listened in stunned silence, offering only tepid applause. It was an unprecedented public dressing-down – effectively, a stern moral audit of his own central administration. By shining light on these dysfunctions, Francis reinforced to the world why his reforms were necessary, and he put corrupt insiders on notice that he saw through them. Notably, far from weakening his hand, these confrontations strengthened his populist appeal and thus his leverage.

Of course, not all of Francis’s reform ambitions succeeded. Bureaucracies have inertia, and the Vatican is no exception. Changing laws is easier than changing mindsets. Firing incompetent or corrupt staff in the Holy See remained notoriously difficult (canon law and Italian labor protections make Vatican employment nearly a life tenure). A plan to streamline communications stumbled, as venerable media institutions (like Vatican Radio and the newspaper L’Osservatore Romano) struggled to adapt to a unified structure and digital focus. Cardinal Pell’s tenure as reform czar was cut short by his legal ordeal, and his replacement – a Jesuit economist, Fr. Juan A. Guerrero – continued the work mostly outside the limelight. There were also internal turf wars: efforts to consolidate various departments sometimes led to new bureaucratic rivalries over competencies. And despite new protocols, major scandals still erupted (e.g., in 2023, a costly construction contract at the Vatican revealed cronyism, reminding everyone that new rules only matter if enforced). Late in his papacy, even Francis grew frustrated that some changes were slow. “A lot of new rules have been introduced, but the question remains whether they have really been implemented,” admitted the ex-auditor Milone, reflecting on the mixed outcomes of the financial reforms.

Still, by 2025 Francis had undeniably bent the arc of Vatican governance toward transparency and accountability. The Vatican Bank, once synonymous with secrecy, was regularly passing international anti-money-laundering inspections – Moneyval gave encouraging reports that the Holy See was complying with global financial norms. For the first time, the Vatican published detailed annual financial statements (small steps in the grand scheme, but revolutionary by Church standards). And critically, Francis showed that a Pope need not be captive to the Curia. He proved a pope could discipline even princes of the Church (as seen with McCarrick’s laicization for abuse and Becciu’s public disgrace for corruption) and could push through administrative restructuring with persistence. He also internationalized the Curia’s staff, quietly bringing in more lay experts and bishops from the global South into Vatican roles, diluting the Italian old guard’s dominance.

In summary, Francis approached the Vatican as a seasoned operator confronting a sclerotic institution: he combined structural reform, personnel shifts, and moral rebuke to achieve an overhaul that many predecessors only dreamed of. An intelligence brief might assess that he “achieved significant disruption of entrenched networks and imposed a new operational culture, though pockets of resistance and the test of enforcement remain”. Importantly, he rooted these reforms not just in efficiency but in theology and mission – insisting that the Curia’s purpose is evangelization and service, not self-serving careerism. This reframing gives his changes a lasting rationale that future popes can invoke. Whether the next administration will build on his reforms or roll them back will depend on whether they perceive this new model as an asset or a constraint. But for now, Francis’s legacy as Reformer-in-Chief is that he dragged the Roman Curia – kicking and screaming – into a new era of (relative) transparency and service, using every tool at his disposal: spiritual exhortation, bureaucratic jiu-jitsu, and when needed, the hammer of papal authority.

Confronting Crisis: Abuse Scandals and Global Challenges

The Abuse Scandal – A Test of Nerve: Among the gravest internal crises Francis faced was the long-simmering clergy sexual abuse scandal and the associated cover-ups by bishops. This was a crisis of credibility for the Church across multiple countries. Francis inherited a situation where his predecessors (John Paul II and Benedict XVI) had been criticized for inaction or insufficient action. Initially, Francis’s approach was somewhat halting – he spoke often of compassion for victims and zero tolerance, but early missteps raised questions about his resolve. The breaking point came with the Chile affair in 2018, which Francis later acknowledged was a major failure on his part. In that case, he defended a Chilean bishop, Juan Barros, accused of covering up abuse, even calling the allegations “calumny.” His vigorous defense backfired; survivors and even some of his own advisers lambasted the Pope for being woefully misinformed. Realizing he had been misled by local bishops, a chastened Francis pivoted dramatically: he dispatched investigators to Chile, received a scathing report on the abuse cover-up culture there, then summoned all Chile’s bishops to Rome. In an unprecedented move, all the Chilean bishops offered their resignations in May 2018 after Francis accused them (and himself) of “grave errors” in handling abuse. This episode showcased Francis’s ability to self-correct and act decisively under pressure. He removed Barros and several other Chilean prelates, meeting personally with abuse survivors to apologize.

Learning from that, Francis convened a global summit on clergy abuse at the Vatican in February 2019, bringing together bishops from around the world. There, he laid out 21 reflection points and later issued new church laws (the Vos Estis Lux Mundi motu proprio) to hold bishops accountable for negligence in abuse cases. He also abolished the pontifical secret in abuse trials, aiming for greater transparency. Critics note these measures, while positive, still rely on bishops policing themselves and on the Vatican’s willingness to enforce discipline. The Pope did use his authority to laicize high-profile offenders, most notably Theodore McCarrick, a former U.S. cardinal – something that would have been unthinkable a few decades prior. Yet, survivor groups and some media continued to press the Vatican on inconsistencies (for example, why some bishops accused of cover-ups in places like Poland or Italy were not removed as swiftly). In an intelligence-style assessment, one might say Francis approached the abuse crisis with a “contain and address” strategy: admit past failings, create structures for accountability, and project an image of penitence and reform. He did not, however, upend the Church’s hierarchical judicial system as some hoped (there is still no independent tribunal solely for trying bishops on abuse charges, a gap analysts flagged as a “major flaw” in the Vatican’s justice system). Nevertheless, by the end of his papacy, Francis had arguably gone further than any pope in confronting this shame – holding a public penitential liturgy for abuse, meeting scores of victims around the world, and ousting even cardinals and archbishops who fell short. Opponents attempted to exploit the scandal (most notably in 2018, when a former nuncio, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, issued a bombshell letter accusing Francis of ignoring McCarrick’s misconduct). Francis famously responded with silence to Viganò’s broadside and let his record speak for itself. Over time, the furor abated as it became clear that Francis had in fact removed McCarrick and was not shielding abusers. By forthrightly admitting mistakes (e.g., in Chile) and then taking action, Francis managed to prevent the abuse crisis from completely derailing his broader agenda, though it remained a stain on the institution that he struggled to erase fully.

Pandemic Leadership: The global COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) was another unforeseen crisis that tested Francis’s leadership mettle. As nations went into lockdown, so did the Vatican. Francis, a pope who loved wading into crowds, suddenly found himself speaking to empty courtyards via camera. In March 2020, in one of the most haunting images of his pontificate, he walked alone in a rain-soaked St. Peter’s Square – normally teeming with Easter-season pilgrims – to deliver an extraordinary Urbi et Orbi blessing for the world, praying before a crucifix that had survived a plague centuries ago. His words that evening captured the world’s attention: “We have realized that we are on the same boat, all of us fragile and disoriented… but we are all called to row together,” he said, urging people to see the shared nature of the threat. This message of solidarity and spiritual reflection on modern society’s priorities resonated widely. Francis framed the pandemic as an opportunity to “rethink the economic and political framework” that had produced glaring inequalities, pointing out how the crisis laid bare a world where the poor and the planet suffer while the rich distance themselves. He continually emphasized caring for the vulnerable – whether that meant advocating vaccine equity between nations or cautioning against a “myopia of partisan interests” as countries responded to the emergency.

During the pandemic, Francis also showed a pastoral flexibility that endeared him to many. For instance, he supported creative ways for the faithful to practice devotions at home, and he temporarily granted special indulgences and permissions (such as general absolution in emergency field hospitals). Internally, he sped up the Vatican’s adoption of remote work and digital communication – a minor administrative feat in such a traditional place. The Pope’s personal bout with illness (he had a serious colon surgery in 2021 and later struggles with chronic sciatica and knee pain) also made him a patient among patients; he was often seen in a wheelchair from 2022 onward, which created a poignant image of frailty even as he pressed on with an energetic agenda. Through it all, Francis maintained a steady drumbeat: urging that once COVID subsided, the world should not return to “normal” as before, because normal was a social order fraught with injustice and environmental ruin. In this, he tried to leverage the crisis to advance the principles of his 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’ (on ecological conversion) and his 2020 Fratelli Tutti (on human fraternity). Whether leaders heeded this call is debatable, but Francis cemented his role as a kind of global moral compass during the pandemic, offering empathy and challenge in equal measure.

Geopolitical Conflicts and Mediation: Pope Francis’s tenure coincided with numerous international crises – wars and political upheavals – where he often attempted to intervene or at least make the Church’s voice heard. Notably, he used the Vatican’s long-honed diplomatic channels to facilitate historic breakthroughs. A prime example was the Cuba–U.S. rapprochement. In 2014, with the Cold War-era standoff thawing, Francis and his diplomats acted as go-betweens for Washington and Havana. He wrote personal letters to President Barack Obama and President Raúl Castro urging resolution of humanitarian issues and offering the Vatican as a neutral ground. That same year, delegations from the U.S. and Cuba held secret talks in the Vatican which helped seal the deal to restore relations. American officials acknowledged that Pope Francis “played a key role in healing the breach”, calling the outcome “the biggest success for the Vatican’s diplomacy in decades.” This achievement harkened back to the Vatican’s role mediating a territorial dispute between Chile and Argentina in 1984 – interestingly, a conflict Bergoglio himself had lived under. For Francis, it was a diplomatic win that boosted the Holy See’s credibility as a small but significant peacemaker on the world stage.

However, not all of Francis’s diplomatic forays were universally praised. His approach to China was particularly controversial. In 2018, the Vatican under Francis reached a provisional agreement with the People’s Republic of China – a Communist regime that does not recognize Vatican authority – concerning the appointment of bishops. This deal was aimed at ending a decades-old schism between China’s state-backed “Patriotic” Church and the underground Church loyal to Rome. In effect, the Pope agreed to share some influence in the selection of Chinese bishops (granting Beijing a say, while the Pope retained a final veto). It was a bold realpolitik move, reflecting Francis’s willingness to “bet on dialogue” even with an officially atheist regime. Many observers compared it to Nixon’s opening to China, seeing Francis as similarly pragmatic. Yet critics, including Cardinal Joseph Zen of Hong Kong and some U.S. officials, lambasted the accord as a capitulation – accusing Francis of “remaining silent on human rights abuses…in exchange for a deal.” Indeed, since 2018, Beijing continued to harass underground Catholics and even violated the agreement by appointing a couple of bishops unilaterally. Francis largely avoided public confrontation with China, repeatedly saying relations were “very respectful” and expressing “great admiration for Chinese culture.” His stance can be interpreted as a long game: he likely calculated that establishing a foothold of cooperation in China, however imperfect, was better for the Church’s future than moral grandstanding that Beijing would ignore. This reflects the mindset of a consummate operator: incremental progress through engagement, at the risk of criticism for not speaking out more forcefully. Only history will judge if Francis’s China strategy yields fruit (e.g., a reunited Church in China) or if it enabled further repression.

Regarding Russia and the war in Ukraine, Francis again walked a fine and often perplexing line. He made history by meeting Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill in 2016, bridging a 1,000-year divide between Rome and Moscow. That meeting in Havana, Cuba was hailed as a breakthrough in Catholic–Orthodox relations and was part of Francis’s broader effort to heal Christian divisions. But after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Francis had to balance his condemnations of the war with his desire to keep dialogue open with Moscow. He voiced sorrow for the “martyred Ukrainian people” and dispatched envoys to try mediating prisoner exchanges. Yet he studiously avoided naming President Vladimir Putin as the aggressor, and once referred to the cultural greatness of “Mother Russia” in a way that infuriated Ukrainians, who accused him of echoing imperialist tropes. Francis defended his approach by saying one must not close the door to diplomacy. He even refrained from harshly criticizing Patriarch Kirill, who justified the war, urging him instead not to be “Putin’s altar boy” – a remark mixing rebuke with familiarity. This cautious Vatican line frustrated some Western observers, but it’s consistent with the Holy See’s traditional diplomatic neutrality and Francis’s instinct to keep channels open at all costs. Indeed, he offered the Vatican as a venue for peace talks and maintained backdoor communications with the Kremlin. Some Vatican insiders likened Francis’s position to that of a mediator who cannot alienate one side if he hopes to broker peace. In intelligence terms, he positioned the Vatican as one of the few global actors that could talk to both Kyiv and Moscow – a potential interlocutor if a stalemate ever brought both parties searching for an off-ramp. Whether that role materializes remains uncertain, but it underscores his strategic patience.

Francis’s outreach to the Islamic world was another diplomatic front. In February 2019, he achieved a milestone by visiting Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates – the first papal visit to the Arabian Peninsula, the birthplace of Islam. There, he co-signed with the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar (Sunni Islam’s leading theologian) the Document on Human Fraternity, a pledge for Christian-Muslim cooperation for peace. This initiative won him considerable respect in Muslim-majority countries and could be seen as a strategic effort to ally religions against extremism. In 2021, he made a daring trip to Iraq, including meeting Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, a revered Shia cleric. That encounter behind closed doors in Najaf sent a powerful signal of solidarity across faiths. The imagery of the Pope in war-torn Mosul praying among ruins, and his plea for Iraqi Christians and Muslims to rebuild their nation together, enhanced the Holy See’s standing as a bridge-builder in a region weary of conflict. Moreover, Francis took a personal interest in South Sudan’s peace process: in April 2019, he famously knelt to kiss the feet of South Sudan’s rival leaders during a spiritual retreat at the Vatican, begging them to keep their fragile peace. The war-hardened politicians were stunned into silence as the 82-year-old pope, despite chronic knee pain, humbled himself physically to encourage their unity. This almost theatrical act of humility was risky – had it failed to move them, it might have looked impotent. But it left an indelible mark on those leaders’ consciences. (South Sudan’s President later said that moment would be remembered as Francis “begging them to make peace”, a testimony to the Pope’s unique modus operandi.)

Overall, Francis’s handling of global crises and diplomacy reveals a tactical dualism: he could be both outspoken (denouncing a “culture of indifference,” calling out populist nationalism) and circumspect (avoiding direct confrontation with powers like China or Russia). He was willing to leverage the moral authority of his position in some cases – for example, starkly criticizing the idea of border walls, stating that those who build walls “are not Christian”, which was widely understood as a critique of former President Donald Trump’s immigration policy. The Vatican under Francis even termed some Western policies (like mass deportations of migrants) a “disgrace.” These strong words showed he did not shrink from clashes when human dignity was at stake. Yet, the same Pope carefully avoided enraging Beijing or Moscow, believing that silent diplomacy might save lives down the line. This adaptive strategy made him hard to pin down politically – he transcended the usual left-right labels on the world stage, frustrating both ideological camps at times. In sum, Pope Francis navigated crises by combining moral clarity with pragmatic engagement. Whether dealing with a scandal inside the Church or a war outside, he sought to keep stakeholders at the table and maintain the Church’s ability to play a healing role. This nuanced approach is a hallmark of a shrewd institutional operator: knowing when to yell and when to whisper, when to break tradition and when to invoke it, all in service of higher goals.

Managing Factional Warfare: Traditionalists, Conservatives, and the Francis Method

If Pope Francis was a reformer and diplomat externally, he was also a battlefield commander internally, contending with factions that opposed his every move. The traditionalist and ultra-conservative opposition to Francis formed almost immediately after his election and persisted throughout his pontificate, at times quite vocally. Understanding how he dealt with this internal resistance is key to appreciating his political skill. Unlike popes who enjoyed relatively uniform support within the Church’s upper echelons, Francis faced the unique situation of a living predecessor (Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) who had a devoted conservative fan base. This unprecedented dynamic emboldened critics: they had a sort of figurehead in the shadows (even though Benedict pledged silence, his very existence in the Vatican Gardens was a rallying point). Francis himself quipped that “some wanted me dead” and were already plotting for the next conclave while he was in the hospital. He only half-jokingly acknowledged the reality that a segment of the hierarchy fundamentally wished for his pontificate to end.

The fault lines were both theological and stylistic. Conservative Catholics, especially in the U.S. and parts of Europe, were suspicious of Francis from the start – he appeared to downplay doctrinal rigor, lived in an unorthodox way, and prioritized issues (like social justice, climate change) that they felt were peripheral to the faith. They “grimaced” when he ditched the red velvet mozzetta cape on Day 1 and “gasped” when he washed women’s feet shortly thereafter. An early headline in Italy’s conservative daily Il Foglio declared, “We don’t like this Pope”, capturing the sentiment of a contingent that soon started calling him “the Dictator Pope” (the title of a scathing 2017 book by an anonymous traditionalist author). This group accused Francis of governing autocratically while preaching mercy – an irony that did not escape notice. Indeed, Francis could be imperious in decision-making when he thought the cause justified it, a trait his opponents seized on. They painted him as a revolutionary undermining tradition and a nepotist surrounding himself with yes-men. Francis, for his part, seemed to almost relish some of this criticism as confirmation that he was shaking up a complacent system. “It’s an honor if the Americans attack me,” he once remarked wryly, referring to the particularly outspoken clique of U.S. conservative Catholic media and donors who opposed him.

One of the early flashpoints was his 2016 apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia, on family life. In a cautious, footnoted way, that document opened the possibility for divorced and civilly remarried Catholics in certain cases to return to receiving Communion after discernment – a small pastoral adjustment that nonetheless touched a nerve in Catholic moral teaching. Some conservatives indeed accused Francis of heresy for this, believing he effectively loosened Jesus’ teaching on marriage indissolubility. The most notable protest came from four cardinals (Raymond Burke, Carlo Caffarra, Walter Brandmüller, and Joachim Meisner) who sent him a set of formal questions or “Dubia” in 2016, asking for clarification on whether traditional doctrine was still intact. They published the dubia when Francis did not respond. This was nearly unprecedented – princes of the Church publicly pressuring the Pope. Francis, true to form, maintained silence and never answered the dubia directly. Critics saw that as evasive; supporters saw it as wise, refusing to dignify what he viewed as a misguided interrogation. Over time, two of the dubia cardinals died, and the issue gradually moved to the background as local bishops implemented Amoris as they saw fit. Francis’s gamble was that, by not engaging in a theological slugfest, he would diffuse the rebels’ momentum. In large part, this worked – the Church did not split, and many bishops quietly adopted Francis’s pastoral approach to remarried couples.

Francis also deftly removed or sidelined key institutional opponents. Cardinal Burke, a figurehead of traditionalism who openly criticized Francis’s agenda, was removed from his post as Prefect of the Apostolic Signatura (the Vatican’s supreme court) in 2014 and given the nominal, powerless position of Patron of the Order of Malta. Burke later lost even that role after a clash with the Vatican in 2017. Similarly, Cardinal Gerhard Müller, a moderately conservative head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, found his five-year term not renewed in 2017, an unusual non-renewal that was seen as Francis making room for someone more aligned with his vision (Müller had resisted some of Francis’s approaches, including on handling of certain abuse cases and theological matters). Neither Burke nor Müller were given much explanation – a sign that Francis, when he deemed necessary, would act unilaterally and unapologetically to remove roadblocks. He instead promoted those who were loyal or at least shared his pastoral outlook. Over the course of his papacy, he appointed over 85 cardinals (out of ~130 electors), the vast majority of voting-age cardinals by the end. Many of these appointments were bishops from the global South or pastoral figures often overlooked previously. For example, he elevated men like Blase Cupich of Chicago and Joseph Tobin of Newark, who were known for their pastoral and moderate stance, while bypassing more traditional candidates. He even named cardinals in places that had never had one (e.g., the first cardinals from Myanmar, from Tonga, from Luxembourg, etc.), thereby diluting the Italian and curial bloc that had long dominated papal elections. This was a strategic personnel policy: by changing the College of Cardinals’ composition, Francis was securing a legacy beyond his lifetime, aiming for a future conclave that would elect someone sympathetic to his reforms. An analysis in 2025 noted that one of Francis’s enduring legacies is “he greatly expanded the diversity of cardinals who will elect his successor,” making the body less Eurocentric and more tilted toward pastors from the developing world.

However, Francis did not simply rely on carrots and sticks; he also tried to outflank his critics with popular support and doctrinal framing. He often rebuked the attitude of rigid traditionalism without naming names. In various speeches, he lambasted those who “safeguard the ashes” of the past instead of keeping the flame alive. He warned against a “rigidity born from fear of change” – clearly alluding to certain seminarians and younger clergy attracted to old liturgical forms and scholastic certainties. In 2021, he took the dramatic step of issuing the motu proprio Traditionis Custodes, which reversed Benedict XVI’s allowance of the old Latin Tridentine Mass. Francis placed strict limits on the use of the 1962 Missal, arguing that the leniency Benedict had shown in 2007 was being abused to foster disunity. This decision stunned the traditionalist Catholic communities devoted to the Tridentine liturgy. They reacted with dismay and even defiance, claiming that Francis’s actions were driving a wedge, not fostering unity (indeed, an article pointed out his insistence on unity was seen by critics as actually causing more division). But from Francis’s perspective, he was eliminating what he viewed as a parallel church that rejected Vatican II. It was a calculated risk to neutralize a potential source of ideological resistance by dispersing it. Enforcing Traditionis Custodes fell to local bishops, and while some U.S. and French bishops chafed against it, most complied. Francis later doubled down, issuing clarifications that further clamped down on the old rite. In doing so, he showed that despite his irenic smile, he could play hardball on matters he deemed crucial for the Church’s direction.

Throughout these struggles, one of Francis’s favored tactics was simply enduring criticism without direct confrontation, which had the effect of robbing his opponents of oxygen. He exhibited a kind of disciplined patience (one could say indifference in the Ignatian spiritual sense) to slights and campaigns against him. For example, in 2019 when a group of traditionalist academics and clergy signed an open letter accusing him of heresy, the Vatican response was minimal – the initiative fizzled in the wider church. When former Vatican officials like Cardinal Müller penned manifestos implying Francis was veering from truth, he carried on undeterred. And when Archbishop Viganò’s incendiary letter of 2018 tried to implicate Francis in covering up abuse (and called for his resignation), Francis famously told reporters, “I will not say a single word about this,” and urged them to judge the facts. His bet was that Viganò’s claims would not stand up to scrutiny and that dignifying them with a papal rebuttal would only elevate a divisive sideshow. Indeed, over time, Viganò’s narrative did lose credibility in many quarters, and Francis’s refusal to be provoked appeared wise.

Behind the scenes, Francis also engaged in key appointments to doctrinal and liturgical offices to ensure his vision was implemented. For instance, after removing Cardinal Müller from the Doctrine office, he eventually appointed Jesuit theologian Cardinal Luis Ladaria (and later a moderate Bishop, Victor Fernández, in 2023) to lead it, virtually guaranteeing no internal doctrinal condemnation of his initiatives. He reconstituted the Pontifical Academy for Life and other bodies, appointing members who supported his broader social teaching outlook (this too caused backlash, as some accused him of stacking decks and purging members). But Francis likely saw these bodies as previously stacked against his approach, so he was simply righting the ship.

By the time of his final years, observers noted that Francis “tried to blunt the opposition and consolidate his progressive reforms” especially after Benedict XVI died in December 2022. Freed from the delicate situation of a retired pope in the background, Francis moved swiftly. In early 2023, when some conservative cardinals once again issued new dubia (questions) on hot-button topics like blessings for same-sex couples and women’s ordination, Francis responded with a detailed letter – but then when the cardinals published their grievances, the Pope simply proceeded with the Synod on Synodality meetings, where those topics were discussed with broad input. He even allowed (in 2023) that there could be circumstances to bless homosexual unions (while not equating them to marriage), an opening that triggered a rare public rebuke from a collective of African bishops who said they would not comply. Francis didn’t punish those bishops; he let the disagreement be aired, betting that time and dialogue would iron it out. Indeed, he often said he welcomed criticism if it was made in love for the Church, and he invited free debate at synods – a contrast to the atmosphere under John Paul II where open dissent was muted. “If you look at all the history of the reform of the church, where you have the strongest resistance… it’s usually a very important point,” noted Sister Nathalie Becquart, a close collaborator of Francis in the Synod process. By that logic, Francis treated resistance as a sign he was touching something significant, and he did not back down easily.

In synthesizing Francis’s handling of internal opposition, one can see a multi-pronged strategy: tolerate and outlast the noise, remove or marginalize the key instigators, change the playing field through new appointments and structures, and continue pushing forward so that opposition is always reacting to him (and not vice versa). He outmaneuvered would-be usurpers not by open confrontation (which could have led to open schism or more Benedict vs. Francis showdowns in the public eye) but by a mix of judo and firm strokes. By the time of his death, even his strongest critics had to admit that Francis had changed the Church in ways they would struggle to reverse. They might attempt to influence the next papal election – likely “maneuvering to ensure someone more sympathetic to their sensibilities” becomes pope, as one analysis put it – but Francis had dramatically increased the College of Cardinals with his allies. In essence, he executed a “political pincer movement”: from above, shaping the future electorate and from below, winning the people’s support through his pastoral popularity, thereby isolating the middle management that opposed him.

The result is that, even though a subset of Catholics will remember Francis as a contentious figure, he maintained overall unity in the Church. No formal schism occurred on his watch, despite alarmist predictions. Traditionalist communities, while unhappy, mostly remained in communion with Rome (albeit some teeter on the edge). Francis’s bet that kindness, patience, and strategic pressure could hold the broad Church together while reforms take root seems to have paid off. In a confidential tone, one could assess: Pope Francis successfully neutralized internal threats to his agenda through a calibrated campaign of personnel changes, selective silence, and assertive policy when necessary, ensuring that his vision would endure beyond his reign. His methods confirm his reputation as “The Consummate Operator” within the often byzantine world of Church politics.

Comparative Perspectives: Francis Among Peers and Predecessors

Francis vs. John Paul II – The People’s Popes: Pope John Paul II (1978–2005) was in many ways Francis’s benchmark for global influence. Both men had an innate ability to connect with crowds and project moral authority on the world stage, yet their styles and contexts differed significantly. John Paul II was a Cold Warrior and showman – a Polish pope who played a pivotal role in the downfall of Soviet communism by inspiring the Solidarity movement and partnering with Western leaders like Ronald Reagan. He wielded hard power through soft means: dramatic pilgrimages to his oppressed homeland, stirring speeches about human rights behind the Iron Curtain, and a charismatic media presence that made him a superstar. Francis, by contrast, came of age in the Global South during a time of neoliberal capitalism and cultural secularism. He did not face a monolithic foe like communism, but rather diffuse challenges like climate change, migration crises, and a Church losing relevance in many parts of the world. Both popes were master communicators, but Francis’s signature images – embracing the disfigured, washing feet, carrying his own suitcase – projected humility and approachability, whereas John Paul’s famous images – kissing the ground of nations, speaking to millions at World Youth Days – projected strength and paternal charisma. Strategically, John Paul II centralized authority heavily in Rome to guard doctrine (often silencing theologians and movements he found wayward), whereas Francis attempted to decentralize some decisions to local bishops and promoted open debate (for example, allowing frank discussion at synods that John Paul likely would have squelched). Nevertheless, Francis was as forceful as John Paul in areas he considered non-negotiable (Francis upheld traditional teachings on abortion, marriage, and priesthood even as he changed tone). Both also showed a knack for geopolitical maneuvering: John Paul II’s Vatican aligned with the U.S. at times (anti-communism) but also opposed the Iraq War in 2003; Francis aligned with the U.N. on climate and refugees, and opposed nationalist policies like Trump’s border wall. ach in his era expanded the papacy’s role as a global player, but Francis did so not by confronting superpowers, but by infiltrating global moral debates—on the economy, the climate, migration, and dignity—wielding the same moral authority, but in a horizontal register rather than vertical proclamation.

Francis vs. Benedict XVI – The Strategist vs. the Theologian: Where John Paul II was the actor-pope and Francis the field marshal of the margins, Benedict XVI represented the professor-pope: deeply intellectual, liturgically refined, and committed to preserving doctrinal continuity. Benedict’s 2013 resignation—a shocking break with papal tradition—paved the way for Francis, but it also cast a long shadow. Many of Francis’s most vocal opponents were effectively Benedict’s ideological or institutional protégés. While the two men expressed mutual respect, their differences were stark: Benedict prized clarity of doctrine; Francis favored moral discernment and pastoral ambiguity. Benedict sought to rescue Catholic identity from relativism through reaffirmation of tradition; Francis often blurred lines to meet people where they were, to the dismay of doctrinal purists.

Strategically, Benedict was cautious—perhaps even conflict-averse. He preferred to lead by writing and example, hoping the inertia of the system would follow. Francis, by contrast, led by disruption, understanding that institutions only move when power is exercised. Benedict made gestures toward reform but was overwhelmed by the dysfunction of the Curia, famously declaring he lacked the “strength of mind and body” to govern. Francis embraced the chaos and retooled it, sometimes using it as cover for maneuvering. In the intelligence metaphor: Benedict was a signal analyst; Francis was HUMINT—embedded, patient, and unafraid of risk.

Francis vs. Global Political Figures – The Asymmetric Moral Actor: On the world stage, Francis’s leadership style often mirrored asymmetric strategic behavior: using moral leverage to influence institutions much larger than himself. In this sense, he invites comparison with figures like Barack Obama, Xi Jinping, and even Vladimir Putin—though ideologically disparate, all understand narrative warfare, legitimacy, and soft power.

- Like Obama, Francis mastered charismatic signaling: a clean image, poetic metaphors, and meta-leadership through tone-setting. Both were seen as reformers more than ideologues. Both governed amid backlash from entrenched establishments they tried to bend toward new priorities.

- Like Xi (in reverse), Francis undertook a massive internal purge and institutional restructuring, but from the margins inward rather than from the center out. Xi consolidated power through nationalism and coercion; Francis did so through humility and pastoral decentralization. But both understood how systems calcify, and how strategic appointments—especially across generations—reshape future governance.

- With Putin, the comparison is more strategic than ethical: Francis, like Putin, understood long games, optics, and the use of inconsistency as a tactic. Where Putin feints unpredictably to confuse adversaries, Francis deploys ambiguity to create room for pastoral flexibility and discourage premature opposition.

What separates Francis from these figures, however, is his moral restraint. He wielded papal power not to dominate but to reform; not to impose, but to recalibrate. But make no mistake—he was every bit as calculating, as effective, and as committed to reshaping the structure beneath him. The world underestimated Francis, just as some underestimated Xi in 2012 or Obama in 2008. What followed was a durable realignment.

…

Legacy and Strategic Assessment, Part I: Institutional, Doctrinal, and Strategic Foundations

Pope Francis leaves behind a Catholic Church that is structurally reshaped, doctrinally reframed, and strategically repositioned—but also internally fragmented and awaiting consolidation. His tenure did not produce revolution, but irreversible recalibration: a re-anchoring of the Church’s global center of gravity, mission priorities, and political alignments. The transformation he engineered did not rely on formal decrees alone, but on a sophisticated matrix of personnel, procedural rewiring, and perceptual management—hallmarks of a long-game institutional operator.

Institutional Legacy: From Papal Court to Service Bureaucracy

Francis’s most enduring institutional legacy is architectural: he tore down the last scaffolding of papal monarchy without destroying the edifice of Roman centrality. The 2022 apostolic constitution Praedicate Evangelium codified a vision of the Curia as a support body for global episcopal mission, not a sovereign court above it. In doing so, he institutionalized subsidiarity in form, if not always in function. He flattened the hierarchy, reorganized Vatican departments into more collaborative dicasteries, and explicitly opened top positions to laity and women—breaking centuries-old assumptions about clerical exclusivity in governance.

But the deeper legacy lies in the culture he forced upon the Curia. Where once titles conferred permanence and power, Francis introduced performance uncertainty and ideological filtering. Curial actors, even senior ones, found themselves exposed to rotation, early retirement, or reassignment based not just on competence, but on alignment with papal priorities. This did not produce pure meritocracy—nepotism and dysfunction persist—but it imposed a psychological awareness that the old playbook no longer ensured survival.

He also removed the financial opacity that long shielded Vatican corruption. The Secretariat for the Economy and the Becciu trial became symbolic litmus tests. Though not all corruption was eliminated, the implicit deal of silence and impunity was broken. Senior officials now live under a regime of surveillance, audit, and reputational exposure—fundamentally altering risk calculus within the Vatican’s elite.

Doctrinal Legacy: The Art of Strategic Drift

Doctrinally, Francis governed with a paradox: he changed everything without changing anything. Not a single major doctrine was reversed under his watch, yet the tone, scope, and social meaning of Church teaching shifted dramatically. This was doctrinal drift by pastoral saturation. He exploited the elasticity of catechetical framing, symbolic emphasis, and episcopal discretion to bend Catholic perception around new norms—especially on topics like LGBT inclusion, migration, economic justice, and environmental stewardship.

Through documents like Laudato Si’, Fratelli Tutti, and Amoris Laetitia, he advanced a non-doctrinal magisterium: shaping the conscience of the Church without touching its canon law. Amoris Laetitia in particular became the prototype of ambiguity as a doctrinal strategy—vague enough to permit interpretation, permissive enough to enable change, yet anchored in tradition to avoid schism. This balancing act was not weakness; it was intentional diffusion, allowing bishops’ conferences to implement as they saw fit—essentially outsourcing doctrinal application to local governance.

This made Francis both revolutionary and deniable. When criticized by traditionalists for doctrinal vagueness, he could—and did—point to continuity. But the pastoral ground shifted: divorced-and-remarried Catholics returned to Communion; LGBT blessings were quietly authorized in some jurisdictions; environmental destruction was equated with sin. Francis changed the world’s understanding of Catholic priorities by weaponizing the hierarchy of values, not its formal content.

Strategic Doctrine: From Fortress to Field Hospital

Francis’s papacy rejected the fortress model of Catholic identity—a vision prominent under John Paul II and Benedict XVI—in favor of what he famously called a “field hospital after battle.” This metaphor became mission doctrine: the Church was to heal first, diagnose later; encounter before judgment; listen before teaching. His decision to open the Synod process not just to bishops but to laypeople and even non-Catholics reflected this shift. Synodality, as he envisioned it, was less a form of democratization than a psychological deflation of papal omniscience—a redistribution of attention, if not authority.

In international strategy, this translated to the Church no longer acting as a sovereign moral empire, but as a globally embedded conscience actor—inserting itself into UN summits, refugee camps, warzones, and border crises not with condemnations but with moral triangulation. The result: Francis repositioned the Church as a power among powers, not above them, and in doing so, extended its relevance far beyond its doctrinal followers.

In short: Francis’s legacy at the institutional and doctrinal level is that of a systemic realignment artist—not tearing down doctrine, but rotating it into new axes of emphasis, and retooling the machinery of the Church to protect and amplify that shift. He succeeded not by force, but by erosion of resistance and curated inevitability.

Legacy and Strategic Assessment, Part II: Adversarial Neutralization, Global Repositioning, and Final Strategic Assessment

If the first half of Francis’s legacy lies in restructuring systems and bending doctrine, the second is found in his domination of adversarial terrain, both within and beyond the Church. Here, his strategy was pure Jesuit: asymmetric, indirect, methodical, and patient, aimed not at frontal conflict but at repositioning the center so that resistance exhausted itself by degree.

Neutralizing Internal Adversaries: The Long Game

His method: absorb, outlast, and outmaneuver.

- Absorb: He allowed open dissent (e.g., the Dubia, Viganò letters, traditionalist manifestos), refused to retaliate publicly, and framed disagreement as permissible in a synodal Church. This disarmed critics rhetorically, depriving them of martyr status.

- Outlast: He understood that many of his loudest critics—especially the aging clerical elite—had no electoral path to restore their influence. He delayed, distracted, and allowed death or resignation to silence them naturally. By 2025, the number of active traditionalist power brokers had diminished significantly.

- Outmaneuver: Most crucially, he changed the composition of the electorate. With nearly 85 new cardinal electors appointed by him—many from the global South and non-traditional dioceses—Francis reshaped the next conclave into a continuation, not a counter-revolution.

The 2021 restriction of the Latin Mass (Traditionis Custodes) was a case study: issued after years of patience, framed as a move to preserve unity, but with devastating precision—it isolated traditionalist movements without elevating their status to full opposition. Francis turned ideology into administrative marginalization, and left opponents out of position. His silence, when attacked, was not retreat. It was containment.

Global Power Repositioning: Vatican as Soft Superpower

On the world stage, Francis repositioned the papacy from a spiritual monarchy aligned with the West to a non-aligned, moral micro-state with global legitimacy. This was not symbolic; it had strategic effects:

- He counterbalanced U.S. hegemony by vocally opposing Trump-era nationalism, border walls, and militarism—without directly confronting the American Church. He leveraged populist critique to build credibility with the Global South and with secularized Europe.

- He engaged authoritarian regimes (China, Russia, Gulf states) through silent diplomacy, often taking criticism from human rights groups but preserving the Church’s operational space—especially in China, where the 2018 agreement, however flawed, re-established minimal canonical unity after decades of state bifurcation.

- He reframed the papacy as a neutral platform—offering mediation in Venezuela, Ukraine, South Sudan, and between Islamic and Christian institutions. Francis’s visits to war-torn states and majority-Muslim nations were part of a moral deterrence strategy: even when powerless militarily, the Pope could disrupt narrative legitimacy.

This geopolitical repositioning weakened the Westphalian assumptions of Vatican foreign policy. Francis didn’t try to act like a sovereign state; he acted like a non-state strategic amplifier: able to insert influence via moral optics, refugee advocacy, and symbolic gestures (e.g., bringing Syrian Muslim families on the papal plane from Lesbos).

Under Francis, the Vatican acted not as the voice of Catholic Europe, but as the conscience of fractured globalization. It was a strategic pivot—and a quiet severing of the old Cold War alliances with the U.S. foreign policy consensus. From fortress of Christendom to agent of conscience.

Strategic Intelligence Assessment: The Francis Doctrine

From an intelligence and strategic communications lens, Francis should be understood as an operator who achieved systemic change through asymmetrical influence mechanisms:

| Variable | Assessment |

|---|---|

| Operational Style | Jesuitic, indirect control, doctrinal ambiguity, personnel leverage |

| Net Strategic Impact | High – Multiple institutional reconfigurations and narrative reorientation |

| Institutional Resilience Score | 8.5/10 – Structural reform + ideological legacy + cardinal electorate rebalancing |

| Adversarial Threat Containment | Successful – No schism, neutralized high-value opposition through time, appointment, and sidelining |

| Doctrinal Innovation Risk | Low in form, High in effect – Maintained formal continuity while enabling cultural drift |

| Global Realignment | Significant – Moved Vatican from Western pillar to non-aligned moral broker |

| Succession Risk Profile | Moderate-High – Depends on conclave consolidation; traditionalist insurgency possible but weakened |

| Legacy Continuity Probability | Strong – Electorate shaped by Francis likely to choose successor from within his paradigm |

Closing Assessment

Pope Francis was not a reluctant pope. He was a disciplined, methodical, long-range institutional actor who used the cover of humility to move tectonic plates. He smiled while he stripped privilege. He spoke of mercy while reordering the foundations of the world’s oldest bureaucracy.

He did not set fire to doctrine. He turned down the oxygen until it transformed into something else.

If his predecessors governed by fiat or fear, Francis governed by narrative control, personnel rebalancing, and procedural disruption. He wielded silence as a weapon, surprise as a tactic, and praedicate evangelium as a constitutional crowbar.

The consummate operator of St. Peter’s modern era has exited the stage—but his fingerprints are on every page of the institution’s future.